So, it has been two years since the public release of ChatGPT. Long enough that we are starting to take the ability to talk to a computer in unconstrained natural language for granted, but not long enough to really grasp the implications of it. I’m pretty sure that everyone was taken by surprise when large language models (LLMs) blasted through the Turing test and emerged well on the other side with borderline superhuman abilities. A period of adjusting expectations and priorities then followed. For engineers like myself, it meant a competition to learn all the new tech the fastest and grab the juiciest contracts offered by the capitalists. And for the capitalists, it meant untold billions of investments in the AI industry. How could they pass this opportunity when the leaders of said industry, to whom these billions flow, promise to replace most of the current workforce with their products at a minuscule fraction of the cost?

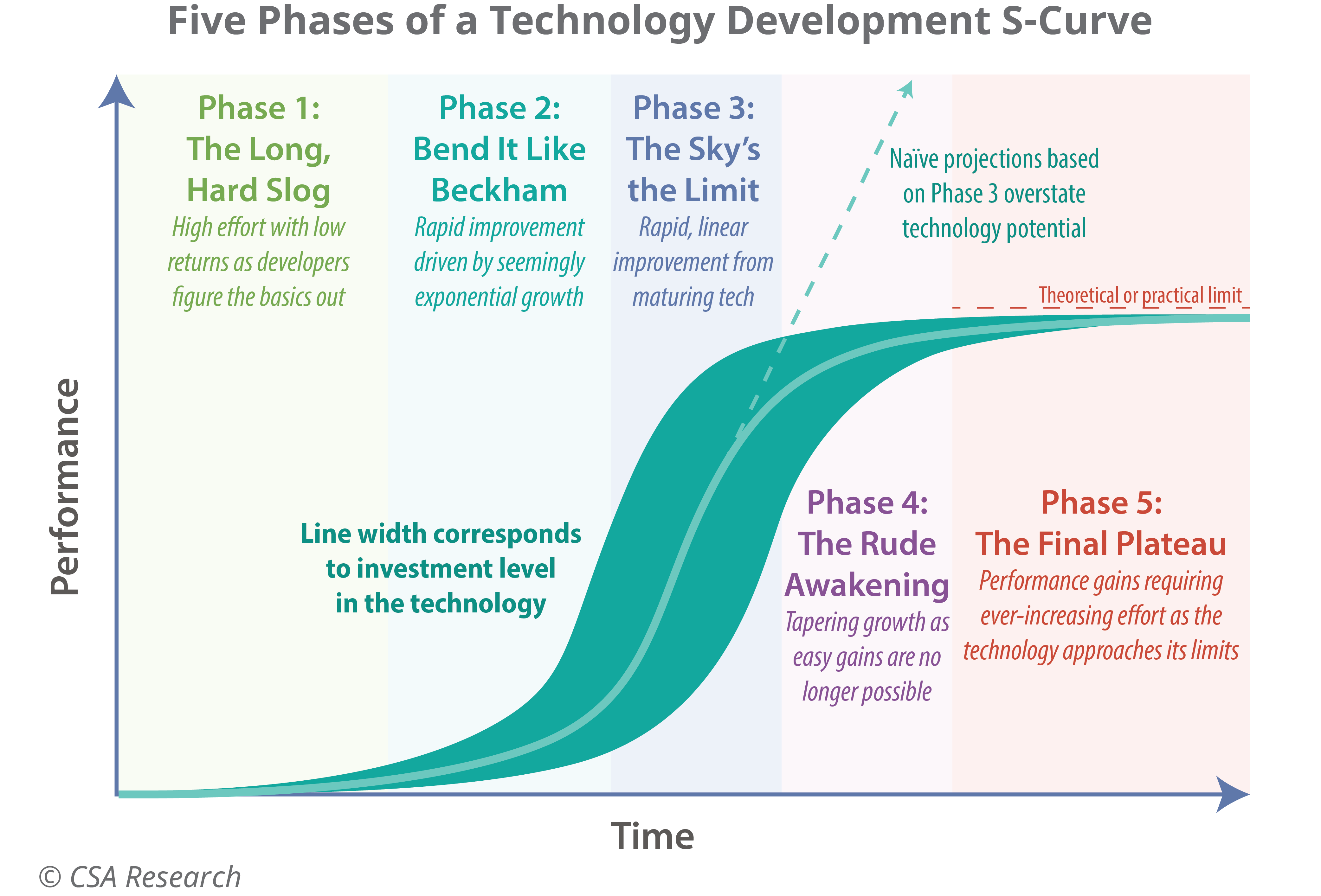

Like every technology before, LLMs are going to follow the developmental S-curve (see the picture above) and are currently in the stage of exponential growth. Most of this growth thus far has been achieved by scaling up the same methods: in other words, more money directly translated to more capable models. Everyone knows this easy growth will end at some point, but the trillion-dollar question is: when?

If the capitalists overestimate how high the curve goes and overcommit to the next step in scale, gigantic supercomputers worth their weight in gold and consuming more power than entire countries may turn into space heaters, and trillions of dollars invested into them and their entire supply chain may evaporate overnight. This would trigger an economic crisis that may forever transform how we see technology and from which the tech industry may never fully recover. Yet far worse is the unlikely scenario if their bet succeeds and this leap of faith actually reaches the holy grail: artificial general intelligence (AGI), a machine that can do pretty much any work that humans can. God help us all if this happens under the current economic system.

These dangers, however, are still theoretical, and there are more pressing problems to worry about right now. The one that feels most important to me is the effects LLMs are already having on education.

Working with junior students, I observed a scary change in them since the release of ChatGPT. Of course, it is only natural that students will use any tools they can get their hands on to cheat the system: we’ve all been there and done that. However, it would be one thing if LLMs could just do any assignment better than the student: then the latter would, in the worst case, learn nothing. What I observe instead is that LLMs are damaging the capabilities that the students used to have, up to and including the ability to think at all. This manifests as giving plausibly sounding non-answers to questions and a shallow approach to problem-solving that betrays a lack of an internal model of the subject. In other words, I observe the students themselves starting to behave like LLMs. And I suspect that they are merely the canaries in the coal mine, the first mass adopters of the technology because the problems they face are perfect use cases for it.

But why are they, exactly? Why is it that LLMs (and especially the new chain-of-thought models like o1-o3 from OpenAI) exhibit borderline superhuman abilities to solve problems specifically designed to be solved, from textbook exercises to the most complex math challenges ever made, yet fail miserably when confronted with real-life, open-ended problems without known solutions (as anyone who seriously attempted to replace human labor with LLMs will attest to)?

One possible reason is that the number of exercises and detailed solutions for them in the training data far exceeds that of real-world problems. This is because academic and practical skills are learned in different ways: the former in a more standardized and documented way, the latter in a more ad-hoc, peer-to-peer, and less linguistic fashion.

Another explanation I am leaning towards is that, when designing problems-to-be-solved, people use some common heuristics that LLMs can pick up and exploit. In geometric terms, the process of problem design traces a geodesic from the answer to the question on some latent manifold that humans are not consciously aware of, and all it takes an LLM to solve the problem is to retrace that line back. Of course, there are no such shortcuts to real-world problems.1

The same conjecture is applicable to pretty much any benchmark, be that one designed for AIs or humans. That’s why I also suspect that it is impossible to design a reliable above-average intelligence test. And not coincidentally, the latest hype wave over LLMs was caused by a new record set by OpenAI’s o3 on the ARC-AGI benchmark, which is highly reminiscent of an IQ test.

Scored 135 first time taking an IQ test - not because I’m a genius but because I’m an Electrical Engineer

byu/Teflonwest301 inmensa

If this is indeed the case, then the incredible performance of LLMs is not at all what it seems, and it is a matter of time until our misinterpretation of their performance clashes with reality. An even worse way to put this is to liken LLMs to parasites precisely tuned to disrupt the very systems that provided their sustenance in the form of training data.

But isn’t it about time for these systems to be disrupted?

The education system sucked anyway

You may be familiar with Goodhart's law, which states, "When a measure becomes a target, it ceases to be a good measure". It captures a very general problem that we face when designing rules for self-regulating systems, be that exams for students, economic policies for nations, or loss functions for machine learning models. The fundamental issue is that there is always a mismatch between what we want to achieve (the target) and what we incentivize (the measure) because if we could incentivize the target directly, we wouldn’t need the self-regulating aspect in the first place.

The education system is a perfect example of this mismatch backfiring. I mentioned in the previous post that we don’t actually know how the education process works: we just teach people a bunch of random things, most of which aren’t directly useful, and hope that they will automagically develop useful abilities as a result. This approach did work for centuries, after all. But even before LLMs, the system was showing cracks.

Firstly, standardized tests and their consequences have been a disaster for the human race have long been a laughing stock for the already educated and a toxic swamp for the students who actually have to take them. The worst offender in my understanding (I never took this test myself and make conclusions from other peoples’ stories) is the Chinese Gaokao exam: not necessarily because it is a bad exam, but more due to how insanely competitive the wider Chinese environment makes it. It breaks my heart just imagining children who have to grind repetitive and largely pointless tasks for 15 hours a day instead of actually living a life. Even the standardized exam that I did take (the Russian YeGE), a much milder version of the same concept, had cases of students killing themselves after failing to pass. And for what? I have yet to meet a university professor who believes that the baseline education level of entrants improved after the introduction of the exam, and the majority firmly believe the opposite. Not to mention a billion-dollar exam cheating industry that sprawls in the shadows of every standardized test. This outcome is completely predictable from Goodhart's law: by making the measure (exam) standardized, we made it feasible to over-optimize for that measure at the expense of general educational attainment, which was the original target.

Another sign of fundamental problems with the education system is the “gifted kids” phenomenon. In short, it turns out that if the education program (the measure) in the junior school years is too easy for a child, they will fail to develop the skills that are actually useful in life (the target) and end up at a disadvantage to their peers later when confronted with real problems.

There is also a strong version of Goodhart's law, stating, “When a measure becomes a target, if it is effectively optimized, then the thing it is designed to measure will grow worse.” The scary phenomenon of students behaving LLM-like that I described before is a clear manifestation of this.

So, LLMs are not an out-of-the-blue game-changer for the education system but merely a straw that is about to finally break the camel’s back. They are the ultimate cheat code, one that can no longer be worked around by stricter proctoring and plagiarism detectors. They are the final call for the education system to change, lest it becomes obsolete.

Ideas on how to reform it have been around for a long time. One is the western STEAM concept, another is a similar framework developed on the Soviet side of the curtain. Both emphasize abandoning memorization tasks in favor of developing independent thinking skills, teaching how to acquire relevant knowledge instead of knowledge itself, and putting hands-on experimental lessons before books. To me, all these recommendations were self-evident even during my own education, but implementing them would mean retraining every teacher, reequipping every school, and rewriting all textbooks from scratch, all in an environment where public education is barely scraping by as it is. Barring a worldwide communist revolution tomorrow, this is not likely to happen.

Then, the best chance we have to attenuate the disaster is to fight fire with fire. To counterbalance LLMs, we would have to develop some other AI systems that cannot be cheated as easily as humans. It sounds terrible because it is: the list of potential ways this could go wrong is at least as long as this essay, and I don’t know how to avoid any of them, but it looks like we won’t have a choice but to figure it out.

But before we can even attempt this, we have to return to the question I have been trying to answer for the last two years: what will LLMs never be able to do? In the previous post, I derived the mathematical answer to it. In this one, I am going to approach from a completely different direction. Instead of focusing on hallucinations of LLMs, let’s instead notice that humans also hallucinate and see how that presents an insurmountable barrier for LLMs.

I know that I know nothing

If you ask ChatGPT to solve some kind of problem without explaining the process and then ask to explain the process in the next query, the explanation you get will have nothing to do with the solution before. In fact, they technically cannot be related because LLMs have no internal state in which this information could have been saved.2 The explanation may coincidentally match the solution, but when it does not or it just doesn’t make any sense, we call it “hallucinated”. And the more I thought about this problem, the more I realized that it is not unique to LLMs: humans do the exact same thing all the time.

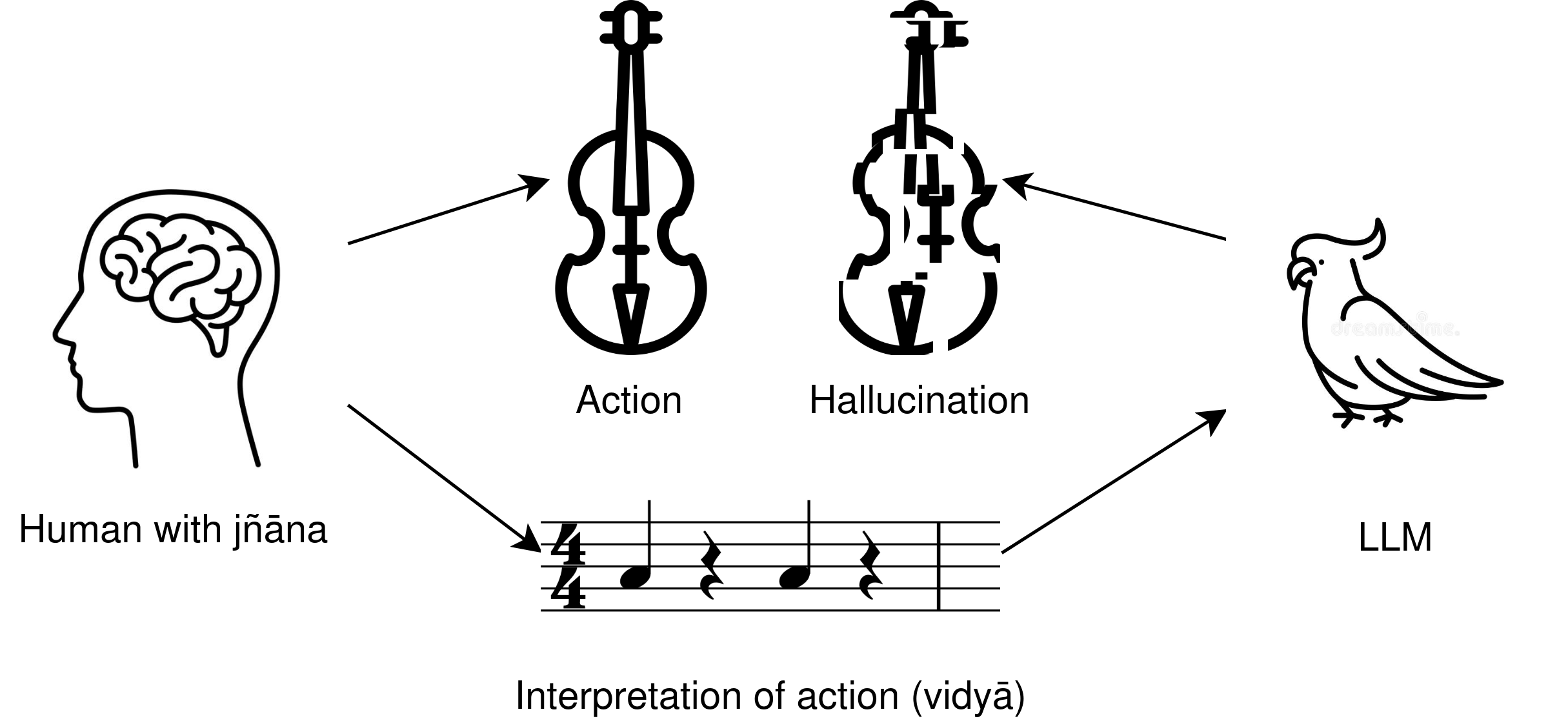

To understand why, we will have to learn two Sanskrit words today. These words are jñāna and vidyā, and both of them translate to “knowledge”. The difference is that vidyā means transmissible knowledge: anything you can find in a book, film, podcast, forum, or dataset. But there is, and that’s what LLM-optimists deny, a second kind of knowledge. Jñāna stands for the subjective, internal knowledge that cannot be exchanged with the outside world. Whenever you attempt to smuggle jñāna out, it simply turns into vidyā, and the process is irreversible: vidyā cannot be converted back to jñāna. Even when a piece of vidyā helps you understand something, that is only because you already had the jñāna onto which it could map. Not all vidyā is linguistic, but all language is vidyā. And the central claim of the Indic gnosiology is that new knowledge can only be created as jñāna.

This is superficially similar to Platonic gnosiology, but the difference is in the epistemology. While Plato and the entire Western line of philosophy following him emphasized linguistic reasoning as the means of uncovering objective truth, the Indic line instead focused on the non-linguistic exploration of subjective truths through practices. Could this be the reason that LLMs mesmerize us disproportionately to their real usefulness? Do we need to dig all the way down to antiquity to explain that? Probably not, but the thought is funny to entertain. And it is probably not a coincidence that Plato keeps popping up in this discussion.

It’s not easy to bring up examples of jñāna precisely because it is, by definition, unobservable and indescribable, but here is an imperfect I came up with. When you are trying to explain what you saw in a dream while still remembering it, your verbal explanation never quite matches what you actually saw. Like dreams, jñāna is produced in the subconscious, with only the end result popping up into consciousness. This is how we get “eureka moments” or “shower thoughts”.

Jñāna is the reason why we cannot actually teach people anything directly; we can only put them into situations where they are forced to generate their own jñāna. This ties directly into the problems of education I discussed in the previous section. Currently, the methodology and metrics of education systems are based on the assumption that the process of learning can be approximated as a mechanical accumulation of vidyā, but any teacher worth their salt knows that’s not even remotely true, that there is something much deeper going on. Ironically, the skill to teach people to acquire jñāna is in itself jñāna, but if we tried to at least think of it in the right way, perhaps we could come up with much better ways to organize the education process.

Do LLMs have jñāna? The purely autoregressive models most likely don’t, but the more complicated models trained with reinforcement learning could. If the ability of the o-series models to reverse-engineer test designs that I hypothesized earlier exists, it would be a good example. But these abilities cannot be transferred to the real world as long as LLMs are perceiving this world through our vidyā. But, as mentioned earlier, vidyā cannot be converted back into jñāna. This means that any skills learned by fitting to vidyā can only be shallow imitations of the real thing, even if sometimes useful: much like every output of an LLM is a hallucination, just some of them happen to match reality.

I will even make a more radical statement: LLMs cannot learn anything useful from data that is itself hallucinated by humans. Soon, I will show how these human hallucinations are all around us, but before that, I want to focus on just one example.

A surprise detour into religions

It’s not hard to guess my religious views, or lack thereof, from my writing. I might have been born a skeptic, as even being brought up in a moderately religious family, I had no inclination to faith whatsoever and merely cosplayed it until it was no longer necessary to conform to my parents’ expectations. But even as a purely ethical system, I had plenty of reasons to be offended by what Christianity had to offer. One thing I found unacceptable is the complete lack of moral value put on animals, whom I always viewed as not that different from us, lacking only the ability to speak. On the other hand, I found classifying mental states like envy, pride, anxiety, or depression as sins to be unfair: not only do they have no victims, but there is nothing I can do to stop them! Or so I thought.

If you had read the short story I posted between these two big essays, you probably wondered what method allowed the protagonist to overcome their fear of water and turn their life around. I left it vague on purpose, but I will also admit that it is a metaphor for my own experience, and for me, that method was Yoga. After taking it moderately seriously for just a year, I already learned to stop panic attacks and the spiral of depression, to cognitively reframe every misfortune on the fly and enter the flow state on demand, things that I would have previously seen as superpowers, and this is only the tip of the iceberg. Within this system, it makes total sense to classify envy, pride, anxiety, or depression as faults of an individual because it gives that individual the power to overcome them.

You see, the thing that positively distinguishes the Indic spiritual tradition (Yoga, Buddhism, Hinduism, etc.) from the Abrahamic one, and why faithless skeptics like myself flock to it, is that it offers practices (what we collectively refer to as “meditation”) that can be followed to achieve objective results without believing in anything supernatural. The problem is that no one can explain in language how these practices work. They were developed by sheer brute force without any theoretical framework to predict what would and what wouldn't work analytically.

And now I am going to make a leap of logic with a high risk of being off. Unfortunately, I can’t afford to get a degree in religion studies just to finish this post, so anyone with a deeper knowledge of the subject is welcome to tell me if this is either a well-known fact or does not fit the data. I will almost certainly laugh at it myself ten years down the line. Still, here goes.

I suspect that the spiritual practices are what came first, most likely developing independently many thousands of times and preceding the development of a class society (in the historical materialist sense). Initially, they were passed down in a peer-to-peer, language-invariant manner. However, as societies developed and the demand for this knowledge grew, teachers had to start putting it into language, but the best they could produce were post-hoc explanations without much useful insight into the underlying processes. These explanations were then passed through oral tradition by people who did not actually participate in the practices, and what eventually came out of this game of telephone was religious mysticism and religions themselves.

As long as the practices were passed down uninterrupted, the practitioners could adjust the mysticism to at least not contradict reality. However, something happened with the development of class society. At some point, these primordial practices that worked without any preconditions were purged, at least from the Abrahamic religions. The likely victims of this purge were the Jewish Kabbalists, Christian Gnostics, and Muslim Sufists, largely because the absence of historical records about them (especially the Gnostics) can only be explained by the deliberate and coordinated destruction of them. The likely motivation for the purge on the part of the ruling class was to increase their power by monopolizing spirituality. If we analyze, say, Christianity through the lens of this hypothesis, many things start to make sense, including those pesky mental sins.

I can’t say if the same process happened in other regions and religious traditions; it only happened to the Abrahamic one and did not happen to the Indic one. The latter could be a result of the Indian caste system being somewhat different from the more common class structure that developed in Europe and the Middle East.

Hold my dataset

So, why did I even go on this tangent about religions?.. Ah yes, LLMs. My point, in short, is that religious mysticism is a hallucination if we use the same definition of hallucinations consistently for humans and LLMs. Why is this important for the discussion? We’ve now established that humans hallucinate, too, and this presents a big problem: it means that not all data generated by humans, regardless of quality, can be trusted as examples of reasoning.

Religious mysticism is merely the clearest example. If I had to generalize, I would say that the class of potentially untrustworthy data is interpretations, meaning post-hoc explanations for practices. Another example that immediately jumps to mind is the interpretations of quantum mechanics. The reason they are useless as reasoning data is that you cannot draw any new conclusions from the interpretations alone (those who do end up neck-deep in quantum mysticism); you need to do the actual math for that.

So, we know that LLMs hallucinate their reasoning when generating a specific response. But we also know that humans do the same. What follows is that LLMs are sometimes learning human reasoning from explanations of it that humans themselves hallucinated!

The one question left is: how much do humans hallucinate, and what percentage of training data out there can be classified as hallucinations? It is easiest to answer it from contrariwise: to identify which data is definitely not hallucinated. The only texts that meet this criterion are the ones that are not interpretations, i.e., not written to explain something after the fact. But if you try to think about it, almost all text ever written is written after the thing it is describing had already happened. The only exceptions are the texts that are self-contained and do not refer to the material reality at all: mathematical problems with their solutions, some source code, and perhaps the most abstract strains of philosophy. An even smaller subset of that small subset, problems with objectively verifiable solutions, are what the o1-o3 model series are trained on. It is also not coincidental that all previous instances of AI systems outperforming humans happened in self-contained problems with known rules, such as in games.

So, I will make a grand statement: LLMs cannot reason about the material world and will never be able to do so due to the nature of how humans produce language. This is to say nothing about future AI systems that gain the ability to interact with the material world directly, without text mediation. They will have their own problems, but we’ll talk about those sometime later.

Combining this with the conclusion of the first section, we arrive at a picture that is very similar to the present-day state of the art: LLMs excel at toy problems, exercises, and benchmarks but struggle to produce anything of real material value.

All this is not a limitation of deep learning itself. What I am really trying to say here is that language is not a shortcut to general intelligence (if such a thing exists at all, but that’s a whole different conversation). To achieve this, we will have to painstakingly tackle every specific problem and slowly and steadily generalize.

It’s hardly surprising that people are seeing LLMs cracking problems that only a handful of humans could solve before and assume that their performance on real-life tasks will be comparable. But this is a mistake that comes from anthropomorphizing algorithms, a mistake that we have made many times before.

Remember when playing chess was used as a measure of intelligence? No? Me neither. I was born around the time that Deep Blue defeated Garry Kasparov, proving that winning chess does not actually require intelligence because Deep Blue clearly did not possess it. And far worse metrics have been used before. Something tells me that, in a decade or two, we will be viewing contest math problems as something not very different from chess: as powerlifting for the brain, something you do purely for self-improvement. After all, we don’t hire powerlifting champions to actually lift stuff; we just use cranes.

-

Yes, deep neural networks can solve different real-world problems, too, by uncovering and exploiting latent manifolds. What I am saying here is that the same method applied to problems-to-be-solved uncovers manifolds of the minds of test designers rather than the subjects of those tests. This works as a solution to test problems, but it cannot be generalized to real-world ones. ↩

-

Of course, I can envision a CoT model using its internal chain of thought saved from the first query to answer the second. In this setup, we would have to ask a different question: can the model explain how it got from one step to another within its chain of thought, which will also produce a hallucinated explanation. ↩