This post is deprecated and left here for the sake of history. If you are interested in the topic, I strongly recommend reading this much more refined article instead.

The Fermi paradox, named after physicist Enrico Fermi, is the apparent contradiction between the lack of evidence and high probability estimates for the existence of extraterrestrial civilizations. The basic points of the argument, made by physicists Enrico Fermi and Michael H. Hart, are:

- There are billions of stars in the galaxy that are similar to the Sun, and many of these stars are billions of years older than the Solar system.

- With high probability, some of these stars have Earth-like planets, and if the Earth is typical, some may have developed intelligent life.

- Some of these civilizations may have developed interstellar travel, a step the Earth is investigating now. Even at the slow pace of currently envisioned interstellar travel, the Milky Way galaxy could be completely traversed in a few million years.

According to this line of reasoning, the Earth should have already been visited by extraterrestrial aliens. In an informal conversation, Fermi noted no convincing evidence of this, leading him to ask, "Where is everybody?" (Wikipedia)

Having studied the vast majority of proposed Fermi paradox solutions, I believe I had found the common misconception that plagues not just them, but multiple seemingly unrelated theories as well. The assumption of rationality.

But first things first. Why should we see any signs of alien activity? Because, whatever their logic and motives may be, they should definitely share a common trait: the tendency for growth. It is either included or follows directly from any definition of life. This implies that any life either stops expanding outward at a certain stage, goes extinct, or simply never occurred before. The latter proposition seems extremely improbable given the age of the universe, and the two former ones are more or less the same, since stagnation eventually means running out of energy and dying. The more you think about it, the scarier this idea becomes.

For now let us assume that our competitors are either dead or never born; that we are the only life within our cosmological horizon; that we are free to make our own choices. Or are we? Can a civilization really make a deliberate choice, especially one that makes logical sense? If we could, wouldn't we already stop wars, hunger, diseases and climate change? We certainly have the science and resources to do so. So why wouldn't we?

Because, like any system, society is not a sum of its members. It is an entity of its own, functioning in accordance with its own rules which couldn't care less about individual humans. Even an ideal totalitarian dictator cannot control the society as a system, let alone the will of the majority. Even though humans are orders of magnitude smarted than ants, humanity isn't much smarter than an anthill when it comes to making decisions. This is what Noam Chomsky calls "Institutional irrationality".

It actually presents an advantage for science fiction writers: even if it's impossible to imagine a being far smarter than oneself, predicting how those beings will behave as a civilization is very much on the table.

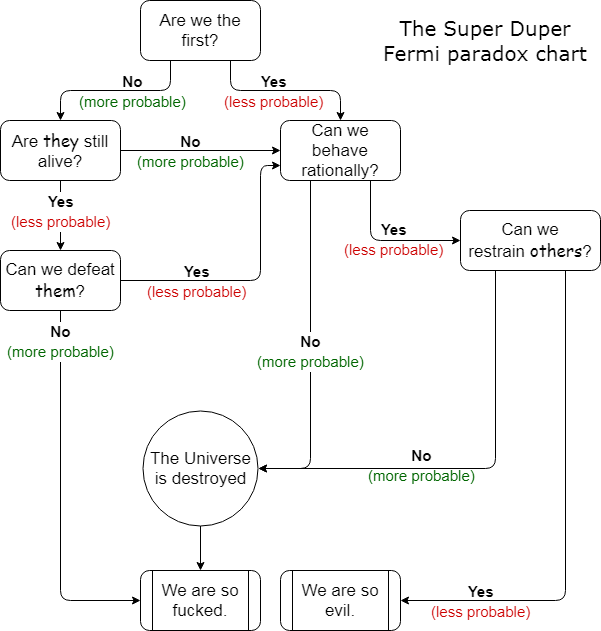

So, how will humans behave in the future? To preserve your likely fading attention, I now have to include a chart that explains my vision for the Fermi paradox, that I will then explain step-by-step:

We've already concluded that, even if humans aren't the first, other species don't seem to have survived long enough to greet us; so our destiny is up to ourselves. The question then is, "Can we behave rationally?", or "Is there a 'cure' for institutional irrationality?". Both answers lead to fascinating conclusions.

First, what if we can't? In short term this would mean suffering all the consequences of climate change and possibly a nuclear war, but is that really enough to completely eradicate humanity? I'm not sure about that. Even a small surviving population can quickly rebuild due to information being virtually indestructible at this point. And even if all humans are dead, other species will be happy to take our place. With more than a billion years of mild sunlight remaining, they should have more than enough time to develop intelligence of their own. Hell, they might even evolve space-faring capability through sheer brute force of natural selection! And being wiped out by superintelligent AI only exacerbates the situation, because that AI would have all our faults embedded it its reward function. It would also be life.

But don't you worry yet, there's another way of destroying ourselves that doesn't rely on sterilizing one particular planet: the way suggested in Tengen Toppa Gurren-Lagann. This must sound like a joke, but bear with me for a while.

One aspect of institutional irrationality is income inequality. It is not a problem with human civilization in particular, but rather a representation of a more general rule: when tomorrow's state of a variable is directly proportional to today's, its distribution follows Pareto's curve. There are good reasons to believe that space economy will follow the same rules: the more fuel you have on a spaceship, the further you can go, the more fuel you can mine on-site, etc. What will wealth be measured in? Matter. With advanced enough technology, the kind of matter doesn't make much difference: nearly everything can be used as fuel or construction material. It then naturally follows that everyone would work toward hoarding as much matter as possible and that some will have exponentially more than others. But what happens when you put too much matter in one place, according to relativity?

A black hole happens.

Black holes are the most likely graves for those who came before us, as well as ourselves. A perfect way to make it seem as if we were alone. This isn't even a "Great filter" anymore, but rather a "Great attractor" — the inevitable trap that every civilization has to fall into, sooner or later.

What would be the point of gathering all the matter in such close proximity to enable a collapse? Simply put, protection. The smaller the surface area of an object in space, the easier it is to defend. "Defend from whom?" Again, extrapolation of our present reality yields this answer easily.

This hypothesis isn't completely untestable, though. Detecting black holes that don't fit our models of galaxy and star formation would be evidence in favor of it. And those black holes may actually exist.

Would an entire civilization collapse into that one black hole? Almost certainly not. But those who remain after the catastrophe won't have much resources to rebuild. And when they do rebuild, the same exact catastrophe will repeat. This cycle effectively makes infinite exponential growth — the bedrock of Dyson dilemma, and, consequently, the Fermi paradox — impossible.

In the process of gathering enough matter we are also likely to devour other inhabited solar systems that haven't yet evolved to our level, the same way a construction crew demolishes anthills before building real estate on their place. The scale of destruction is hard to estimate now, but it might well envelop the entire supercluster. Destroying the entire universe, as suggested by the chart, is theoretically impossible, but it doesn't make much difference. The most obvious counterargument, "But surely an interstellar civilization won't be dumb enough to collapse itself into black holes!", contradicts the assumption we've made by going down this logical branch on the chart above, namely "We can't behave rationally".

But what if we can?

Well, even if we can, others probably don't. And we cannot sit idly by as some alien species is devouring our supercluster. The best thing we can do to benefit everyone is to forcefully stagnate their development, trap them in their home solar system before it's too late. At least that seems to be the only alternative to complete eradication of all alien life.

The Zoo hypothesis and the Matrix now seem much more feasible. Maybe, we aren't alone after all? Maybe, our world isn't really ours? Actually, that might be the best option of all. In this case, we are alleviated from the privilege of making the hard decisions and hard mistakes.